Introduction

Some of the errors I made in the endgame are just burnt into my memory, and I hope I won’t make them again, at least not unless I’m in a severe time trouble. I wanted to analyse those errors deeper and to try to better understand their reasons.

I think the most embarrassing mistakes for me are the mistakes that critical (i.e. change the result of the game) and that are made in a situation that I studied previously and actually know how to win or draw. In this post I’ll follow this format: first some context leading to a position, then the position itself, maybe with a couple of extra moves, then the bad move that I made, why I made it, and finally the right way to play. I will also computer check my analysis.

In order to write and analyse those games now, I first had to find them among all the games I played, which is not trivial if you have many games. For that I used endgame material queries on the database of my games. I previously wrote a post about how to do that, check that out if you are interested.

Mistake #1. Zugzwang and pawn recapturing

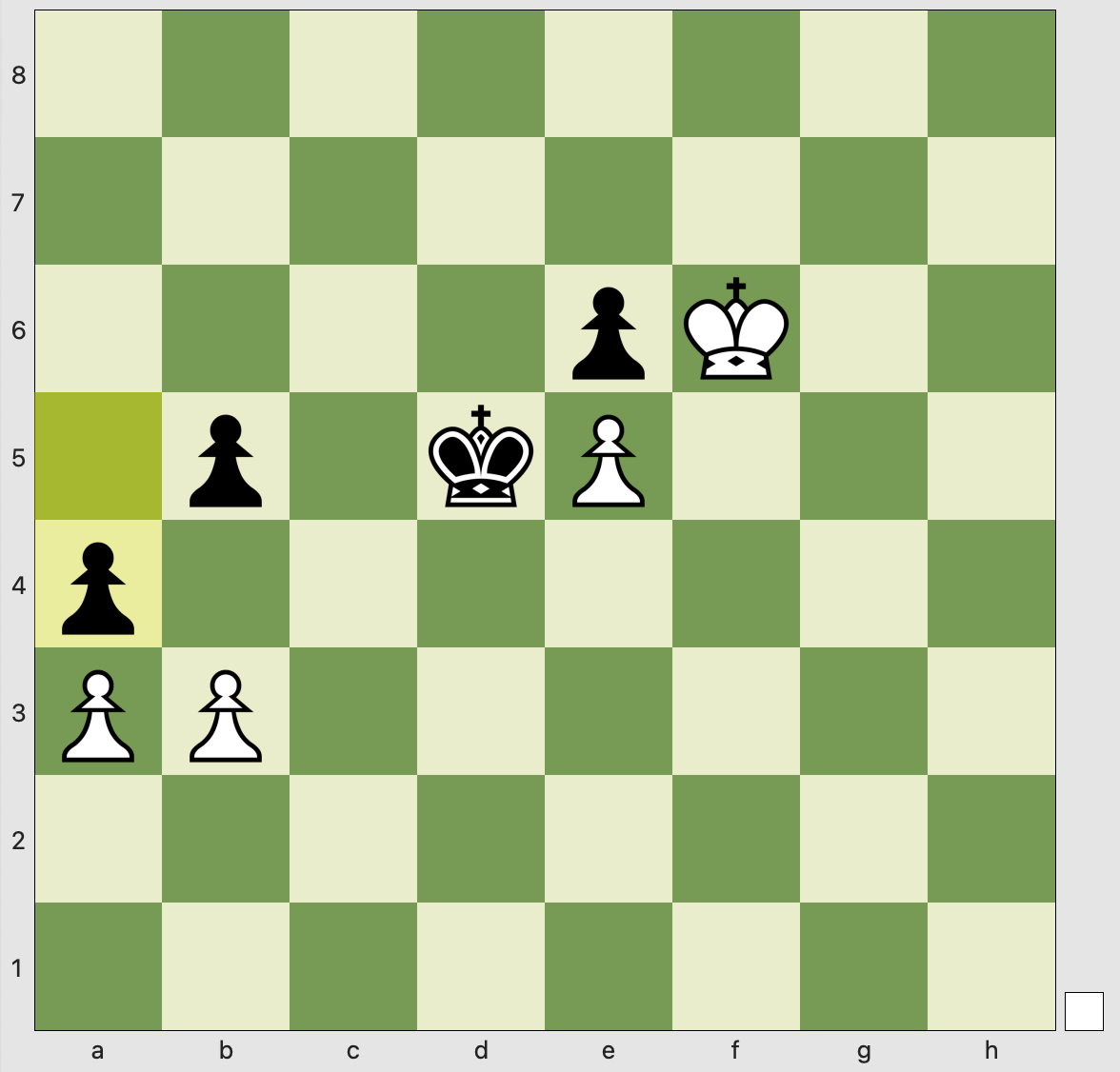

This configuration of Kings and pawns is quite typical and is a good example of a mutual zugzwang. If there is nothing else on the board, then whoever moves loses the pawn, because they have to move the King and abandon the pawn. Silman calls this configuration “Trébuchet” in his Endgame Course book (not sure why).

Let’s now see how this is applicable to my game.

I’m playing White and I just played Kf6, establishing Trébuchet, which is a good move.

If Black plays Kc6 to go after White pawns, I play Kxe6 and I need just four tempos to promote the pawn. Black is much slower and needs eight tempos to promote! So Kc6 won’t do. But Black is not in zugzwang yet, they still have pawn moves, so a good try may be a5. Then I calculated that I can just reply b3, with a symmetrical pawn setup, and if Black pushes any pawn I can deal with it. So we’ve got to the following position next. What would you play as White there? Don’t scroll below the diagram if you don’t want spoilers — I don’t have a better way to hide spoilers yet, sorry.

So, what would you play?

Probably every sane person would just continue with the plan and play b4, blocking the pawns and putting Black in a real zugzwang. Then, tempo counting tells one that White is still quicker to promote (even though Black came closer with the pawns and King since last time we counted), so this must be likely winning for White. It may be somewhat tricky, because the Black pawn would be close to promotion, but still it would a good position to be in.

I was, however, somewhat worried about those prospects and extra calculations, so I decided to simplify and played bxa4?? throwing the win out of the window. I didn’t realise that recapturing the pawns passed the move, so it is now me who is in Zugzwang, and not my opponent! And of course after bxa4, Black recaptured, I had to move my King, I lost e5 pawn and the game.

I think the reason for this particular mistake was assuming that pawn recapture do not pass the move to the other side (just like pushing to b4), I considered them “symmetrical” in a way. And I was so sure in this that I didn’t even bother to calculate. I just played the move, thinking that it’s just simplifying and I’m still on the “right side of the mutual zugzwang”.

For me, there are two lessons here: first the vague “trust but verify”, i.e. it’s always good to check your instincts with the calculation, and the second lesson, more concrete: pawn recaptures may pass the move, so one needs to be careful with them in zugzwang positions and in particular in Trébuchet position.

Mistake #2. Passers, stalemate tricks and psychology

Probably no list of endgame mistakes can be complete without including an accidental stalemate. I think my mistake here is somewhat subtler than just a pure stalemate, but is based on similar ideas.

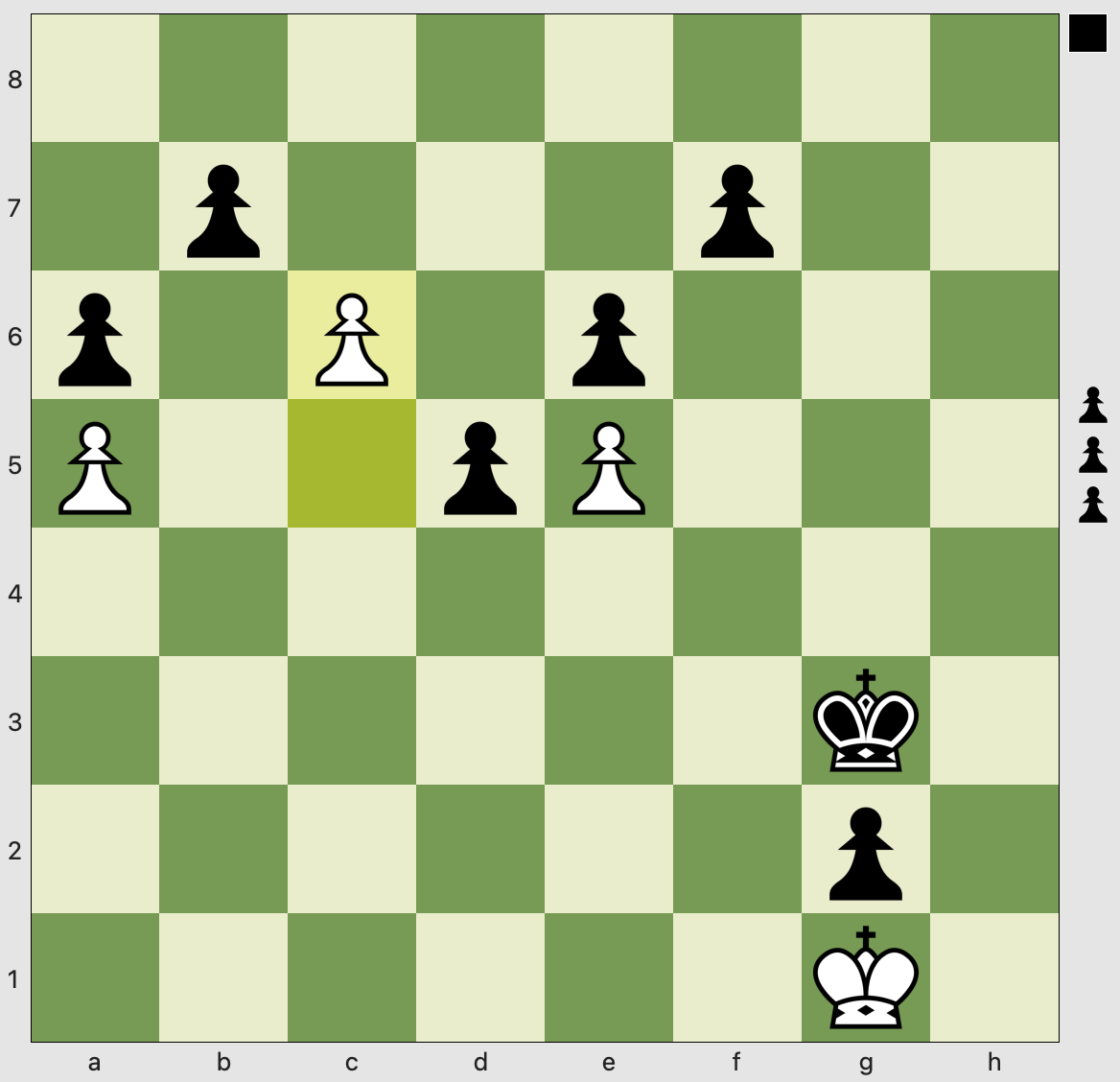

I am playing Black in the following diagram. I have a passer, which I just escorted to the end, but unfortunately can’t promote because of the blocking White King. What would you play as Black?

It’s a very easy win: you just play Ke3, give up that pawn, gobble several more White pawns and promote your e-pawn or f-pawn.

However, I decided to be tricky and thought: “aha, I can play Kg3 and it’s not a stalemate yet, I had some similar tactics problems on ChessTempo before, so I can just let the White pawn moving forward, promote my other pawn and checkmate the King!” Silly? I bet. So I made an unthinkable Kg3 move and got a cold shower after the only possible reply d5, oof:

Now I of course realised that my vague plans about checkmating are not working, because this is a real game and not a beautiful tactical exercise. White pawn is closer to promotion than my other pawns and if I just capture it with either c or e pawn, White moves the other pawn forward and I am in the same situation: I have to either capture and allow stalemate or not capture and allow White to promote. So we played cxd c6. And guess what I did in the following situation?

Of course, here I had to reconsider the game result, just capture and have a draw by stalemate. But it’s hard to reassess the situation realistically after such a distressing turn of events and go from a mindset of “lazily convertying a completely won endgame” to “playing for a draw from a lost position”. So I pushed d4, allowing White to play c7 and promote first. After that White easily stopped my pawns and won the game.

So why did I make this mistake? Because I was influenced by a tactical idea I had often seen in tactical exercises, and was in relaxed “already won” mood and didn’t calculate.

Lesson learned: tactics do not automatically work in real life, just like in puzzles. And another: stalemate ideas as a defensive resource have to be treated with respect, even if it looks like it’s not a stalemate yet, it may very well be after a couple of moves. I think some players like me may develop a somewhat dismissive attitude to their opponents trying to play for a stalemate, because most often this happens when playing a totally winning King+Queen vs King endgame against weaker opponents who never resign. And there it’s easy to avoid stalemate, even in time trouble, because we practiced this ending so many times. But in general playing for stalemate is a clever defensive resource and can be quite useful in slightly more advanced forms.

Mistake #3. Rook endgame with Ben Finegold

OK, I was not really playing Ben Finegold himself, sorry for the misleading title! I was just recalling his video, so he was like virtually standing right next to me when I was playing this game.

I am playing Black here. White has a dangerous passed pawn that they pushed all the way to the 7th, but fortunately their rook is blocking the way and my rook is behind the passed pawn, just as prescribed by The Most Fundamental Rook Endgame Principle.

So how can Black draw this? Do you have a plan? Fortunately enough for me, just a couple weeks before the game I was watching Ben Finegold videos about essential endgames, and a similar position was right where he started.

A natural idea for an uninitiated rook endgame player might be to try to approach and capture a7 pawn with the King with Kf7. But this move immediately loses! See below how.

An important defensive idea here is that Black has to keep the King on g7 or h7, only those two squares! If Black moves to g6, then White rook moves with check to g8, vacates the square for the pawn with tempo and promotes the pawn next, forcing Black to give up the rook.

And if we play our naive move Kf7 (thinking that if White checks Rf8, we just play Kxf8 and grab the rook for nothing), White answers Rh8! With the idea that if rook captures the pawn, we play Rh7+! and skewer the rook (K moves, Rxa7):

And when the King is on g7 or h7 - neither of those tricks works, so those are safe squares for the Black King.

OK, I knew all of that and I knew that all Black has to do here is either to move the King back and forth between g7 or h7, or to make other waiting moves like Ra1-a2-a1-a2, and then I should be able to draw because White has no way of making progress. White can bring the King closer to the pawn, but I should be able to check him away.

So the game was progressing like this: I was making waiting moves with the King and Rook and my opponent tried to do something useful. We exchanged a couple of pawns, and eventually his King came to attack my rook:

And that was actually the question I had while watching the video: what one is supposed to do when this happens. I think Ben didn’t cover it, because it was probably trivial for him. I thought OK, probably I just need to move the rook along a-file and that should be fine, so I played Ra6. That’s not a mistake, the game is still drawn.

Then my opponent tried another approach: attacking the pawns with the King (which sounds promising because my King is tied to h7 and g7 — it can fully defend the pawns). So we’ve got to this:

Here again, I am correctly responding Kg7 (the only move), not allowing Kf6. So far, so good, I am quite happy with my defensive technique, Ben Finegold would be proud!

And now my opponent tries the last trick: just approaching his pawn with the King in order to defend it and free the Rook. What would you play in this diagram as Black?

The right move is of course just go back to the defensive stand and play Ra1 or Ra2, intending to meet Kb6 with Rb1+, so that the King can’t defend the pawn. The King has either to go back to c-file (then we come back with Ra1) or to go to a-file, then we keep checking. And if the King tries to approach our rook and stop the checks, at some point we play Ra6, and go to the position previously covered.

But I played Ra5+ which is immediately losing, do you see why?

Because now the King can play Kb6, defend the pawn and I don’t have checks! And next, when the King defends the pawn, the Rook can finally move out of its a8 jail and White will be able to promote the pawn.

I think the reason for the loss here was that I didn’t fully internalize part of that lesson video, where Ben said that you should check the King immediately when it touches his pawn. Also, while watching the video I was distracted by a question as to what happens when the King comes close to a1 corner and tries to attack the rook, which probably affected my attention for the rest of the video. I should have just set up the position on the board and play through it to make sure I have my questions resolved.

Lesson learned: try to answer your questions right when watching videos or reading books, not during games, when it may be too late or just not enough time to figure out the answers.

Outro

I hope you found those positions entertaining, and my analysis instructive, and I also hope that you won’t make the same mistakes!

I intend to write weekly, so feel free to subscribe. Cheers!