In this post, I want to share what I appreciate most in endgame studies: the battle of ideas between White and Black.

Unlike typical tactical puzzles where a spectacular first-move sacrifice often leads to immediate collapse, endgame studies contain much more. A strong first move is merely the beginning — your virtual opponent responds with active moves, beautiful defences, and sacrifices of their own. These responses can refute your initial ideas and challenge you to find even better ones.

Let's look at an example.

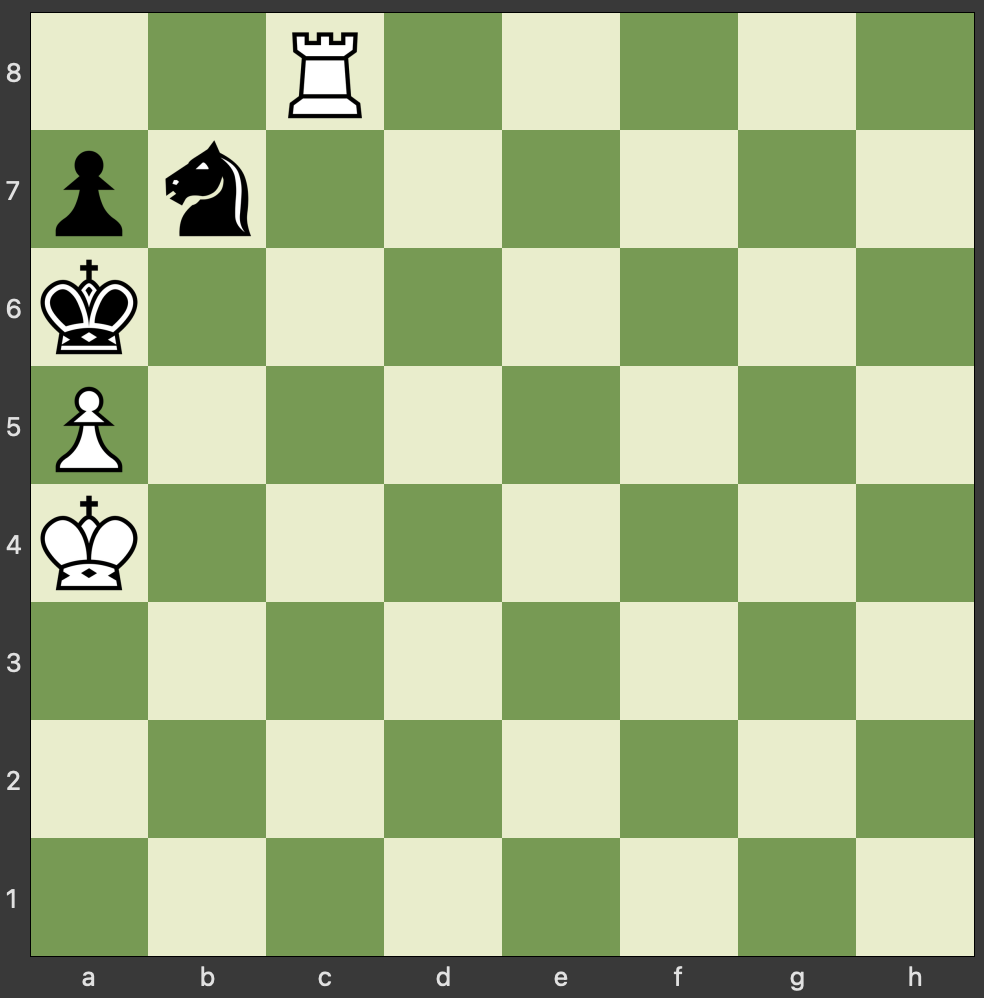

Study #1. Henri Weenink, 1918

Take a look at the following study and try to solve it — or at least come up with a move you'd like to play. White to play and win. Can you find the win?

Let's pause for a moment before revealing the moves:

.

.

.

.

At first glance, you may wonder: why is this even a study? It looks trivial. You simply play 1. c7 and promote next move! The knight sits conveniently on d8, allowing either 2. c8 or 2. cxd8, making the pawn unstoppable. And surely a Queen wins against a lone knight — there are no nasty forks in sight.

But look closer. Can Black counter your Promotion Idea with their own idea?

Indeed they can! Put on your Black hat and consider: what about 1…Nb7! ? If we promote with 2. c8=Q?, it's unexpectedly stalemate! Black fights our Promotion Idea with a Stalemate Idea.

This creates a crucial moment for solvers: when our initial idea is refuted, we reach a crossroads. We can either abandon our original idea and search for something entirely new, or try to improve upon it — finding a way to make it work despite Black's clever defence.

Let's refine our promotion idea. The stalemate only works because of the diagonal pin on the knight. Since we're not forced to promote to a Queen, we can use an Under-Promotion Idea! We can promote to a non-diagonal piece: either a knight or a rook.

Let's try a rook first, as it's more powerful, 2. c8=R:

What can Black do now? They can just snatch the a5 pawn: 2...Nxa5, a natural move, no more fancy ideas, but it looks good enough. We know from Endgame theory that Rook vs Knight endgame is normally a draw when there are no pawns. And here the Knight even has a pawn to boot! So White needs to do something dramatic to win this — we either need to win the knight or give a checkmate.

Can you see what White should do after 2…Nxa5?

.

.

.

.

There are no checks and the King moves allow the knight to escape, so the only forcing move seems to be 3. Rc5! that attacks the knight. And it has nowhere to go: three escape squares are controlled by the Rook, and if 3…Nb7, we have 4. Rc6#.

So it looks like after all, White's Promotion and Under-Promotion Ideas triumphed over Black's Stalemate idea, and we achieved our solution. At this stage, we should look for some more crafty Black refutations, but there are none in this study.

However, remember about the crossroads that I mentioned before. If at any point you couldn't find the win with the Rook, you may have tried the Knight promotion (and seen that it doesn't work). Or maybe you wouldn't even promote at all, impressed by the Stalemate Idea, and play 2. Kb4 instead (as some of the solvers of this problem did). That 2. Kb4 actually looks promising — Black will need to move the knight to d6, and we can attack it with 3. Kc5:

The knight moves to c8 to maintain the blockade, while we can continue advancing with our king. Though this position is ultimately a draw with the knight successfully holding against the pawn, proving this isn't straightforward. Whether you need this line of analysis depends on if you've already found the winning follow-up of the rook promotion. I analysed it solely because a friend suggested it as a solution, and I needed to demonstrate why it draws (a correct study has to have only one solution).

This seemingly simple study, which appeared trivial at first glance, reveals several fascinating ideas elegantly woven into just a couple of moves and six pieces. It shows how crucial it is to analyse both White's and Black's best moves, searching for refutations and counter-refutations — just as in a real game where opponents engage in a battle of ideas.

Let's examine another, slightly more challenging study to further explore this strategic interplay.

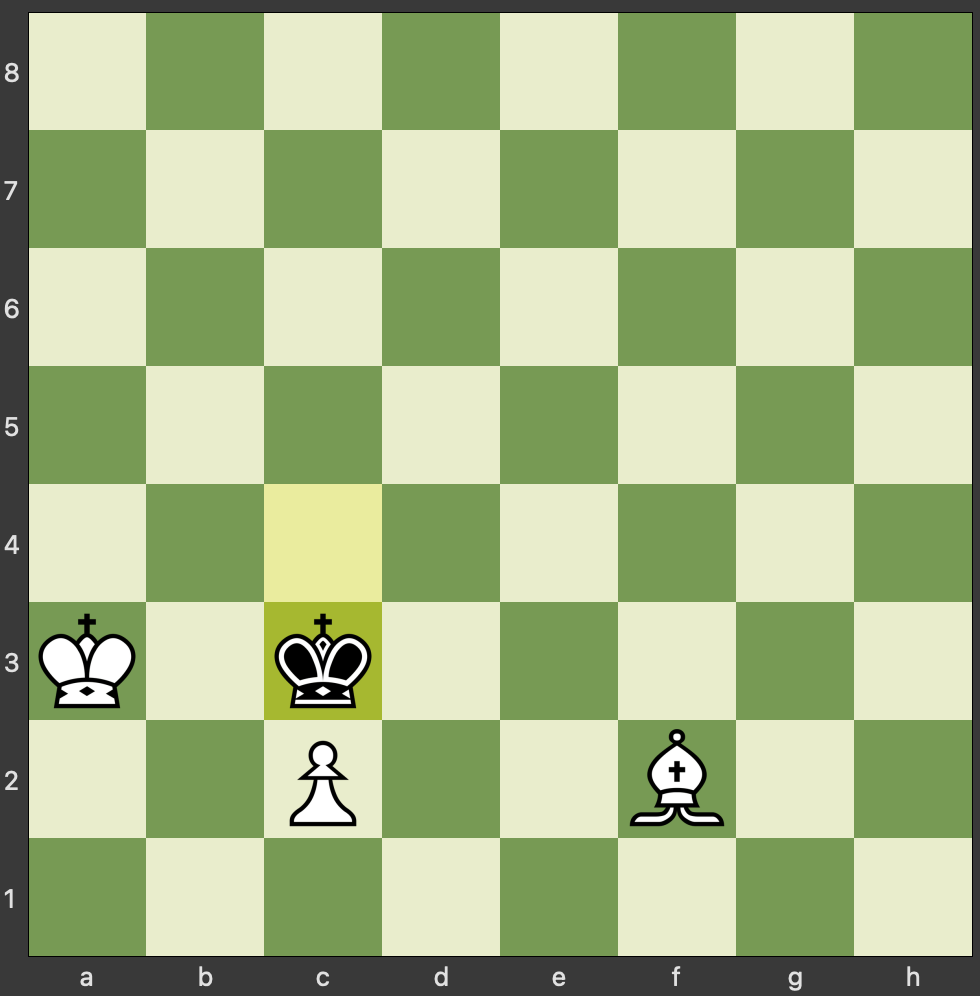

Study #2. Leonid Kubbel, 1934

“I haven't seen this one before but looks like Kubbel’s genius was cranked up to the max when he composed it. So good.” — kiwiPete in ChessGym chat

Try to solve this one on your own. Give yourself a good 15-25 minutes or more before looking at the solution — this is the typical time I use for solving studies.

White to play and win:

As usual, some anti-spoiler space first:

.

.

.

.

And off we go. Material is almost equal, so if we just proceed normally, we are likely to draw this, or at least we can't immediately prove that it's a win. This means that we should win a piece or checkmate. Currently, checkmate looks unlikely, so let's aim to win a piece. If we win a bishop, normally Rook+Bishop vs Rook is a theoretical draw, but we have a pawn as well, so that will be won for White.

An immediate candidate is 1. Ra4, pinning the bishop, with the idea of Be1 next to attack the rook and the bishop behind it. Then surely something has to give and we will win a piece or two.

And another idea is 1. Be1 immediately with the idea of pinning with Ra4 next.

Let's start with 1. Ra4. What can Black do to counter our Be1 threat? They can't defend the e1 square with the Rook and there are no meaningful checks. So seemingly the only thing they can do is to step away from the pin with the King and attack the Rook: 1…Kb4. This looks like a powerful idea; however, we have something even better: 2. Rxb4+! King has to take Kxb4 and then we play 3. Be1 — pinning and winning the Rook for nothing. Then we are left with the Bishop and the pawn, and this is definitely a win:

So, is that enough and can we consider it done? Not yet, Kubbel has some better defensive ideas in store for us! Do you see any other first move by Black that we didn't consider?

.

.

.

.

We didn’t consider 1…Ra3! What’s that, is Black just giving up the bishop?

Indeed, but if we take it (2. Rxa3 Bxa3 3. Kxa3), Black can attack the pawn with 3…Kc3, and White can't defend it. It's a draw — White obviously can't checkmate with a lonely bishop:

Here we see the battle of ideas unfold: White employs the Pin Idea, while Black counters with the Not-Enough-Mating-Material Idea through a bishop sacrifice.

Should we abandon our 1. Ra4 idea or keep exploring it? Let's persist and examine what happens if we decline Black's bishop sacrifice, looking back at the previous diagram.

There is one forcing move for White here: what if we just take the bishop on b4 with check? 2. Rxb4+ Then, the king will take 2...Kxb4, and we will notice that the rook on a3 is attacked by White's King and Black's King is its only protector. So can we try to chase that defender away? Unfortunately, if 3. Be1+, the King can still keep contact with the Rook with 3...Ka4:

Black is very resilient. Do we have to give up here? Not yet, White has one more crafty idea up their sleeve! Zugzwang Idea, which is quite common in studies (and in real games too!). 4. Bc3! is the cherry on top! This bishop move blocks the rook and unexpectedly Black has no moves. If they move the King — they lose the Rook. And the Rook has no squares to go, other than to capture the bishop: 4…Rxc3 5. Kxc3, but then we end up in a winning pawn endgame for White:

Black can't stop 6. Kd4, and we know from pawn endgame theory that when the king gets two squares ahead of its pawn (and the pawn isn't in immediate danger), it's a guaranteed win. The active king and a reserve tempo of the pawn prevent any opposition tricks from working.

What a journey! We've witnessed an array of chess ideas woven together — pins, bishop sacrifices, exchange sacrifices, blocking manoeuvres, zugzwang, and defender-chasing — all culminating in basic pawn endgame principles. It's truly delightful to uncover these battles of ideas on your own while solving such a brilliant study.

I hope you've enjoyed this article. As always, please consider subscribing for more free, quality chess content.